The first camps in Mordovia, such as VISHLON in the Perm Krai, appeared before the GULAG came into being. They were formed because of Moscow’s urgent need for logs. The city was mainly heated by stoves, and logs for them were purchased at special log markets. The shutdown of the New Economic Plan and the ban on free trade destroyed these markets. The responsibility for providing the capital with logs was placed on the OGPU, and the nearest large tracts of forest were found in Mordovia. Near the town of Temnikov, the department of the SEVLON was opened – the Northern Camp of Special Purpose of the OGPU, with the center in Ust-Sysolsk, present-day Syktyvkar, which in 1931 was transformed into the independent Temnikov corrective labor camp.

In 1948, part of the camp sections of the Temnikov corrective labor camp was transformed into Special Camp No. 3 “Dubravny” (Oak Grove), and in the early 1960s, all particularly dangerous criminals were concentrated in ITK ZHKH-385 – the former Dubravny camp.

In the early 1960s, there were 19 corrective labor colonies operating at the ZHKH-385 department – former camp sections of the Dubravny corrective labor camp, retaining the previous numeration. Criminals sentenced for particularly dangerous crimes against the state were held in five of them: at ZHKH-385/3 in the village of Barashevo with two sections and with a central camp hospital, ZHKH-385/7 in the village of Sosnovka with two sections, ZHKH-385/11 in the village of Yavas, ZKKH-385/17 in the village of Ozerny with two sections, one of which – No. 2 – was for women, and ZHKH-385/19 in the village of Lesnoi. Initially, prisoners were allocated according to their charges – different colonies had anti-Soviet, nationalist and collaborator prisoners.

But the situation had changed significantly by the mid-1960s. The majority of anti-Soviet prisoners sentenced in 1957-1969 were released, and their total number decreased considerably, but staunch opponents of the communist regime began to be sent there – those who were later called dissidents. Many of them were members of various groups that were declared to be anti-Soviet – left-wing and right-wing socialist, nationalist, religious and even anarchist and monarchist groups. There were many anti-Soviet and anti-Communist prisoners charged with treason for attempting to flee the USSR.

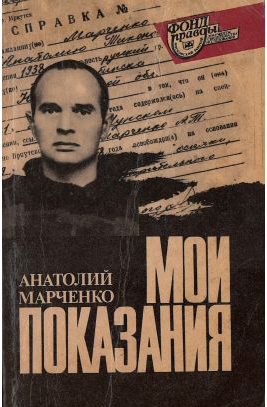

“My Testimony” by A. Marchenko. First published in Samizdat in 1967, and according to historian A. Daniel “it had the effect of an exploding bomb”

In the second half of the 1960s, the first human rights defenders appeared in the camps. They continued to do what they had done at liberty – to fight for human rights, in this case, for the rights of prisoners. The individual struggle of prisoners for their rights did exist before this, and there were cases of fierce collective struggle (a vivid example, with certain reservations, was the uprising in the special camps in 1953-1954), but in the second half of the 1960s in Mordovian political camps, human rights activity became increasingly systematic in nature. Dissidents began to collect information about abuse by camp administration and the struggle of prisoners for their rights, and send this information out into the wider world. The first issue of the human rights bulletin “Chronicle of current events” of 30 April 1968 contained a report about a collective hunger strike in camp point 17 against unlawful deprivations of meetings and confiscations of documents.