In Perm, a young street performer, Yekaterina Romanova, was detained for organizing a solidarity concert in support of the members of the St. Petersburg band “Stoptime.” According to the Telegram channel Perm 36.6, a local pro-war activist filed a complaint against her, claiming that the concert, held on October 22, made him miss his bus.

Following her detention, police charged Romanova under Article 20.2.2 of the Russian Code of Administrative Offenses — for “organizing a mass gathering of citizens in a public place that disrupted public order.” Her court hearing was scheduled for November 1, but defense lawyer Aleksei Ogloblin requested to be summoned to court, and the session was postponed.

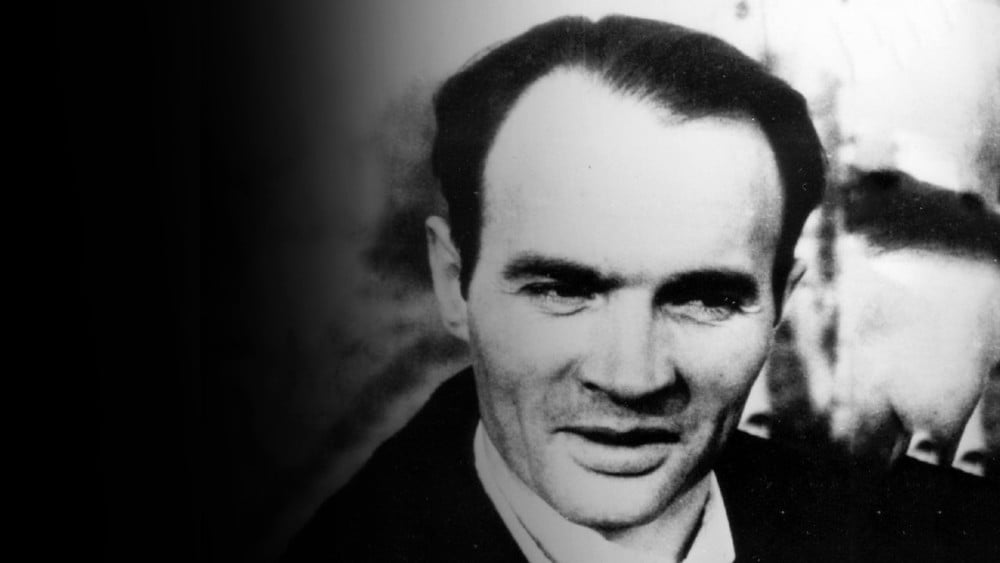

Yekaterina Romanova

The Stoptime group gained recognition for performing songs by musicians labeled “foreign agents” in Russia. Since mid-October, its members — vocalist Diana Loginova (Naoko), guitarist Alexander Orlov, and drummer Vladislav Leontyev — have faced administrative cases for “unauthorized protests” and “discrediting the army.” They have been fined and repeatedly placed under administrative arrest.

After the arrests, street musicians across Russia began performing songs in Stoptime’s support, while bloggers and artists published solidarity videos online.

Photo: Perm 36.6