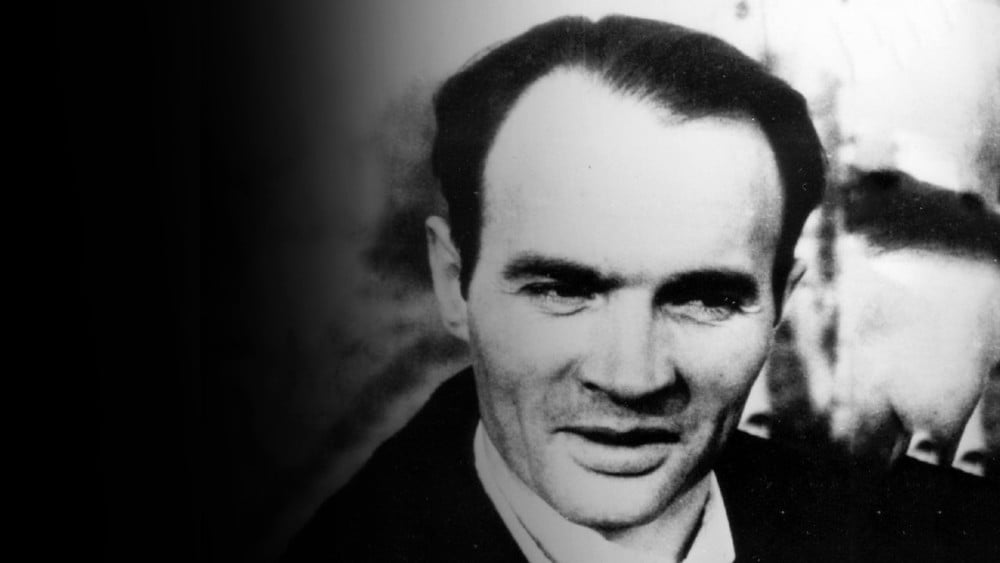

On 5 December 2025, Perm opposition politician and former member of the Legislative Assembly of Perm Krai Konstantin Okunev spent his 57th birthday in a pre-trial detention center. His arrest on charges of “justifying terrorism” raises serious concerns about its legitimacy and is widely viewed by human rights defenders as politically motivated.

Okunev was detained on 29 October and placed in Perm’s Detention Center No. 1 (SIZO-1) by a ruling of the Leninsky District Court, which ordered that he remain in custody until 28 December. The case was opened under Article 205.2(2) of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation — according to investigators, the grounds for prosecution were statements published on his Telegram channel.

Konstantin Okunev has long been one of the most prominent figures in Perm’s opposition. He served in the Perm City Duma and the regional Legislative Assembly, openly criticized federal and regional authorities, condemned political repression and restrictions on civil liberties, and consistently supported civic initiatives and independent activists. For his position, he faced pressure many times, including fines, administrative cases, and public attacks. The current criminal prosecution is the most severe pressure campaign against him to date.

Shortly before his birthday, the Federal Financial Monitoring Service (Rosfinmonitoring) added Okunev to its registry of “terrorists and extremists,” further worsening his situation and imposing additional restrictions — including the blocking of financial transactions — even before a court verdict.

The team of the virtual museum “Perm-36” expresses solidarity and support for Konstantin Okunev. For a person held in isolation, words of support are especially meaningful, especially on such days. We encourage everyone to send him a letter or a postcard.

Address for letters: 614000, Perm, Klimenko St. 24, Detention Center No. 1 (SIZO-1),

Konstantin Nikolaevich Okunev, born 05.12.1968.

Write to political prisoners — it truly matters to them, and it is safe for those who write.